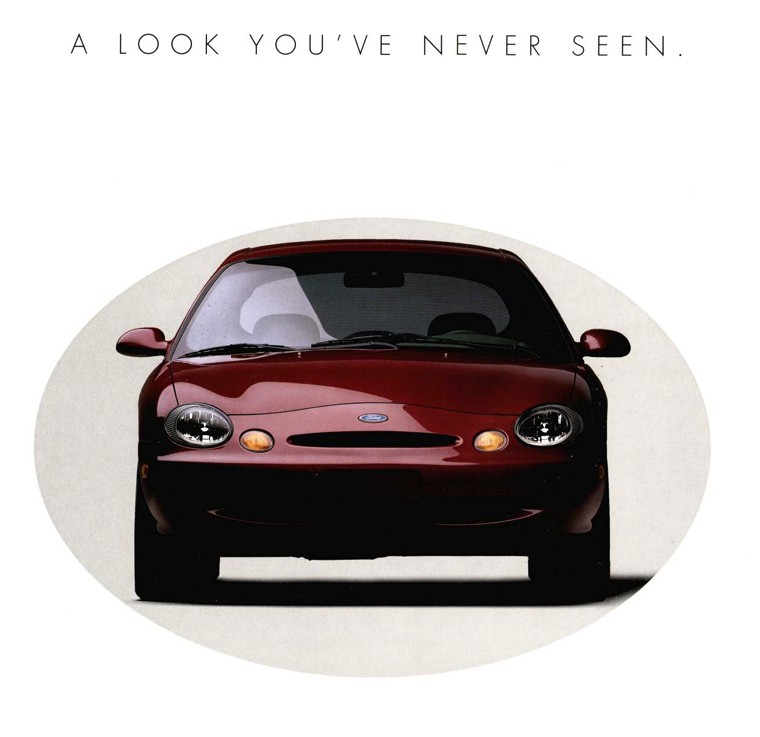

The third-generation (1996–99) Ford Taurus aimed to recapture the groundbreaking spirit of the original 1986 model, a car that redefined the American family sedan. Ford’s rationale for developing this new Taurus was sound; the then best-selling car in America was losing its edge. Many observers even questioned if fleet sales were the only factor keeping the Taurus at the top. The original “jellybean” Taurus design had lost its appeal by the early 1990s, necessitating a complete redesign, potentially pushing the iconic shape even further.

Could the team behind “the car that saved Ford” deliver another game-changer, given the freedom to innovate once more?

The result was the 1996 Ford Taurus. While objectively improved over its second-generation predecessor in many aspects, it stumbled on two critical fronts: cost and public acceptance. The radical new design of the Taurus alienated potential buyers, and traditional fleet customers balked at the increased price, deeming the upscale interior features vulnerable to damage from renters or employees. Perhaps the issues began with Ford’s design inspiration.

The 1991 Ford Contour Concept might have been an example of designers overreaching. The sheer volume of oval shapes and unconventional approaches to car design proved too much for the Taurus’s more conservative customer base. This was unfortunate because the Contour Concept’s design elements were logically translated into the 1996 Ford Taurus, at least in theory.

Despite the polarizingly radical styling, the 1996 Taurus did offer improvements its predecessors lacked, notably in build quality and refinement. The interior was significantly more luxurious, boasting triple-stitched leather seats (not just leather surfaces), soft-touch plastics throughout the cabin, and thoughtful details like a flip-out console inspired by the Mazda ɛ̃fini MS-8 sedan. Noise, vibration, and harshness (NVH) levels were greatly reduced thanks to a much stiffer chassis. Furthermore, the responsive 3.0-liter, four-cam Duratec V-6 engine delivered a class-leading 200 horsepower, outperforming competitors like the Camry and Accord.

Ford was so confident in its efforts to regain dominance in the family sedan market that it even invited a journalist to document the development process. Ford also invested in features like a backlight grille emblem for its sister car, the Mercury Sable. However, this emblem and many other costly features were quickly abandoned to appease fleet managers and boost profitability for shareholders. This cost-cutting drive culminated in the mid-year introduction of the Taurus G trim, as the GL trim levels were deemed too verbose for profitability.

Then there’s the gem of the lineup: the third-generation Taurus SHO. This model came equipped with a V8 engine, an automatic transmission, and added weight. This combination often sparks debate among automotive enthusiasts.

Motorweek reviewed a third-generation SHO in Rose Mist Clearcoat Metallic and praised it highly. They noted the front end’s smoother integration compared to the standard Taurus “catfish face,” the remarkably refined V8 powertrain, the excellent ZF variable-orifice power steering, and the enhanced seats. However, the high-performance SHO model was a bittersweet experience. The very attributes that made the 1996 Taurus a comfortable family car also seemed to dilute the SHO’s once-famous dynamic and aggressive character.

Many enthusiasts criticize the V8 SHO for being exclusively available with an automatic transmission. While a valid point, it’s worth remembering that most V6 SHOs were also sold with automatic transmissions, catering to a broader audience. Moreover, the existing MTX manual transmission was unlikely to handle the V8 engine’s increased torque reliably. Durability concerns were paramount for Ford.

Reliability was indeed the Achilles’ heel of the third-gen Taurus SHO, specifically the Yamaha-engineered V8 engine. While it sounded fantastic, and with exhaust modifications, arguably became one of the best-sounding production V8s ever, it suffered from problematic cam sprockets. These failing cam sprockets in an interference engine design led to the demise of many 1996 Ford Sho models. This is a real tragedy, as there were numerous compelling reasons to appreciate these uniquely styled family sedans.

In conclusion, the 1996 Taurus, and especially the 1996 Ford SHO, was a commendable car with understandable flaws, excluding the significant V8 cam sprocket issue. The styling, while conceptually sound, was too radical for the market, inadvertently paving the way for cost reductions. As costs were cut, the decline accelerated. By the fourth generation in 2000, the distinctive oval rear window disappeared, leather seats became less luxurious, and hard plastics returned to the interior. These changes made Japanese competitors like the Accord and Camry increasingly appealing. Ford’s cost-cutting on the Taurus indirectly contributed to the lasting success of the Accord and Camry.

The third-generation Taurus’s struggles marked the beginning of an era of global automotive platforms. These new platforms prioritized manufacturing efficiency and broader market appeal over unique, regionally specific designs. Why create a sedan solely for North America when platforms could be shared globally?

By the late 1990s, North American automotive distinctiveness was largely confined to trucks and SUVs. The story of the third-generation Taurus and 1996 Ford SHO is a reminder of a pivotal shift in automotive design philosophy, and perhaps a missed opportunity for Ford to maintain its sedan leadership. The boldly contoured ovals of the Taurus, ultimately, were not sustainable against broader market pressures and changing consumer tastes.